Pink Floyd have wafted vaguely through my whole life. Like a heady, psychedelic incense they have always been in the air. They infiltrated my consciousness through old stereos and tape decks and later, when my mother was aware I had a consciousness, through my mother.

My mother had grown up in Cambridge in the ‘60s. A model for Ossie Clarke, the first Flake woman, a purveyor of quick wit and a partaker of LSD, she was one of the cool cats. Stories of Leonard Cohen, Nico from the Velvet Underground and Pink Floyd just drifted over me, as at 12 I had no real concept of who these people were. I was a latter-day cool cat at this point and uninterested in the past. But post my highly acclaimed Ferbie, Spice Girls and Run DMC era, I got Leonard Cohen down by the time I was about 16, Nico – I’m still yet to do; I was about 18 when I first tried to heighten my awareness of Pink Floyd. I went with my sister to the Live 8 gig – had I already been a long standing fan like my sister, I may have enjoyed standing outside the arena listening to the echoed reverbs of 50 year old men, as I was not, I did not particularly. Pink Floyd’s ember was left to glow in the back of my brain a while longer.

Then at the age of 20 a flutter of pages re-ignited my curiosity. I thought maybe I’d enjoy the literature about them more than I had their music, so when the biography ‘Pigs Might Fly’ was released I pinched my mothers’ well-thumbed copy and took it up to London with me. It was moderately interesting for the first 50 odd pages, but having not enjoyed their music and with no real reference to who any of these people were, except my mother who was being referred to as “Mad Sue” by the middle aged, Henry Rollins wannabe of an author, there was little impetus for me to read much more.

At this juncture I’d like to point out I’m listening to Pink Floyd now and, I do think they’re music is a bit, well, for the sake of argument, we’ll say it’s not to my taste. Which disappoints me, I expected more from myself; but I now remember why I regretted syncing my iPod with my dads’ computer.

From what I’ve read however, I like them, I like their lyrics, I like their intention, I like their balls (as in chutzpa – grow up) and I’ve always liked the sound of Roger Keith (Syd) Barrett.

Roger Keith Barrett was born in 1946 in Cambridge. As a child he loved art and as his parents noticed his talent he started attending Saturday morning drawing classes at Homerton College and later attended the Camberwell College of Arts. A month before Barrett’s 16th birthday, his father died, which people reasonably suggest being a potential contributor to Barrett’s later mental instability. Roger Keith, became Syd after the old, jazz double bassist Sid Barrett. Both Barrett and Pink Floyd (as they would become) respectively dabbled in music and bands and Syd joined them in 1965 when they were called ‘The Tea Set.’ Barrett later named them The Pink Floyd Sound, after an amalgamation of the names of Pink Anderson and Floyd Council, who he’d read about on a sleeve of a Blind Boy Fuller EP. Barrett is credited with influencing their psychedelic sound and having all moved to London they became the house band at UFO – where all the movers and shakers got groovy and off their nut, and then later, The Roundhouse. They swiftly became the most popular band of the ‘London Underground’ scene. The band were offered a contract by EMI and their debut single ‘Arnold Lane’ went to number 20, despite being banned by Radio London, their next single ‘See Emily Play’ reached number 6. The bands increasing popularity and vast fan base also increased the amount of pressure on Barrett. He was famous, as his true namesake Roger might have suggested (Germanic elements of Roger mean fame.) Consequentially Barrett’s intake of LSD and his erraticness increased (bouts of depression and schizophrenia were reported) as his level of dedication to the band, as a group, decreased. It decreased to a level where a new guitarist, David Gilmour was brought in to cover for Barrett when he was either physically or mentally AWOL. Barrett’s involvement in the band continued to decrease and in 1968 he left. Barrett made a brief foray in a solo career, coerced by EMI but this don’t last long either. After touring with Jimi Hendrix, sporadic appearances on the BBC and interviews with Mick Rock in the Rolling Stone in which Barrett contested he “couldn’t find anyone good enough to play with” – after his tour with Hendrix, Syd flitted between his home in Cambridge with his mother and London and then finally moved back to Cambridge for good in 1982. On this final return, according to his sister, Syd walked the whole 50 miles back. He secluded in to his burrow, reverting to his love of painting and cherished his privacy. In 2006 he died of pancreatic cancer having suffered from type 2 diabetes for years. Artists such as Paul McCartney, Pete Townshend, Marc Bolan and David Bowie have all acknowledged Barrett’s influence on their work. By many he was and still is called a genius. For me, the first thing that pops in to mind at the mention of his name is a story my mother told me of how he decided to paint his bedroom floor, but started at the door so he eventually painted himself in to a corner. It sounded like something I would do, a sucker for affinity, I liked this kid from the off.

This image flooded back when my friend who works at the Idea Generation Gallery told me they were doing an exhibition on his artwork and love letters to old girlfriends. I was curious, I still wanted to know more about this man who had played an, albeit brief part in my mothers life. So I put myself down.

On the morning of the private view, Radio 4 was as it is always in my house, burbling in the background, Woman’s Hour were chatting away about burkas or something, when I hear the name ‘Jenny Spires,’ my ears prick up. Jenny Spires, one of my mother’s friends and one-time girlfriend of Syd Barrett is talking to Jenni Murray about the exhibition. This is all too exciting for me and I have to lye down for a while. I have a very fine constitution.

Against all laws of chronology, the evening of the private view came around. I, like many others, was genuinely excited to be getting this personal insight. So, to mark this special occasion I put on my finest Yasser Arafat-style bedroom slippers, a flowery little crop top and a leather skirt. Looking truly extraordinary I headed out the door. Within a few steps I’d tripped over. Muttering profanities at the pavement I look down to see the pavement was not culpable and that the soles on my dictator slippers had all but disintegrated.

No time to change them now, I’m making a concerted effort to appear something approaching punctual these days. So looking like a drag incarnation of ‘Steptoe and Son,’ I trip my way to the exhibition.

“Kicking around on a piece of ground in your home town

Waiting for someone or something to show you the way.”

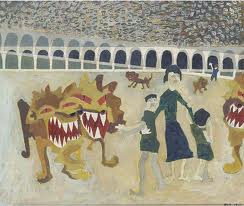

I show me the way and we arrive punctually at 7pm, there are already hoards of people. As is the correct etiquette at a private view, I head straight for the bar and wash warm rum down my throat. One of Syd’s paintings stand out, a picture of two lions lion with a woman and two children standing next to them. I stare at it momentarily and then am jostled back in to the running commentary of …

“Excuse me.”

“Sorry.”

“Do you mind if I just squeeze past.”

“That was my foot.”

“I’ll pay for the dry cleaning.”

A perpetual pigeon in a room of storks, crowds make me nervous, but nerves muted slightly by the Sailor Jerrys I slalom my way through the crowd and head straight to the love letters. They are almost childish in their romanticism, their lack of restraint, with ink pictures of stick couples left for the girlfriend to fill in. Which she does. The majority of his letters are to his girlfriend Libby Gausden, a smaller portion to Jenny Spires, which they had kindly donated to this exhibition.

We go outside for a cigarette and I regale the fascinating story of my battered shoes. The artist currently known as ‘T-Bone’ remarks:

“That’s what happened to Syd.”

“What did?”

“He tripped over his soul.”

Bar a few lines from Syd’s love letters I am quite positive this is one of the loveliest things I’ve ever heard.

With that in mind, we head back in but unable to concentrate properly as my magpie eyes find it impossible to direct their gaze anywhere other than Noel Fielding’s be-jeweled cape, we leave. I promise myself I will return another day.

As that hilarious old chap, Fate would have it, a few days later I receive an email from my mother and subsequently Jenny herself, saying that she would like to meet me and take me to a Q&A, it is at this moment I am alerted to the fact that the exhibition was actually a bi-product of a new biography about Syd Barrett, aptly named ‘Barrett’ by Russell Beecher and Will Shute.

On the day of the Q&A, moments away from the door I receive a call from Jenny asking where I am. I see a woman outside the gallery from behind and make the calculated assumption, as she was also on the phone, that this was Jenny, I cringe as the panto inside me blurts …

“I’m behind yooou.”

Jenny turns round, and either ignores or doesn’t hear what I say. She smiles and gives me a kiss. She tells me it’s lovely to meet me and to come inside. Having not smoked all day I make a quick apology and tell her I’ll follow her in while I clumsily balance coffee, tobacco and liquorice papers. As my mothers elected spokesperson on this earth – I don’t quite feel I did her justice here, and even less so when I discover as I enter the gallery wafting out smog-like smoke from an over-packed rollie, that Jenny wanted to introduce me to people.

The familiar feeling of vague embarrassment and guilt washes over me as I assert I wouldn’t have smoked had I known.

We look at some of the art and pictures, there is one of Syd in a room where the floorboards are all painted bar a mattress-shaped corner in the room. I tell Jenny the story my mother told me and she says that, yes, this is the room. I liked this, don’t know why. Jenny then walks me over to one of her letters, next to it a beautiful picture of her and Syd staring at each other with respective intent. Sunlight coming in from the window behind them. I look at Jenny now, her profile looking at her profile 40 odd years ago and I could see the same girl. The smooth curve of her nose and her soft cheeks. Syd had been a lucky man. We walk away from the picture and over to the scattering of people, while discussing the popularity of the private view Jenny, with amused humility says ..

“Yes, it was very funny, Graham Coxon asked me for my autograph. Should’ve been the other way around really shouldn’t it?”

I disagree.

I meet Russell, who is tall, with a kind voice and sporting a luscious head of raven coloured hair. A conditioned Noel Fielding.

“This is Jade, Sue Kingsford’s daughter.”

It turns out Russell as well as co-writing this book, had also made a film called ‘A Technicolor Dream’ in which my mother featured with a daffodil in her mouth, I profess this is the only part of the film I’d seen. He replies..

“Probably the only part worth seeing.”

I’m sure it’s not, but it makes me laugh.

I head over to the bar, a delayed reaction. Men, ever ahead of the game, are drinking beer, I go dead continental and get a glass of red wine. While a pretty girl struggles to find a corkscrew I start talking to the man next to me, no idea what I said, but it was probably idiotic. I progress from idiocy, to condescend him and say ..

“So what are you doing here? Do you work here or something?”

“I wrote the book.”

“Ah, right. I see….”

This is Will Shute, co-author of the book. He is young, with a shaved head, glasses and a nervous intelligence. As with Beecher, I gauge his intelligence not from the fact that he has written a book (whilst doing a PHD) but from his self-deprecation (which unlike Beecher I haven’t quoted, but it was present.)

He asks me to ask a question.

I hate asking questions at things like this, someone usually asks my question first (and uses shorter words than I would,) or I worry I’ll do something embarrassing while everyone’s looking at me. Like sneeze or spontaneously combust. But I’m no deserter, a loyal soldier I pry my brain for a question, and then remember a quote beneath one of Syd’s paintings I read while I was pretending not to look at Noel Fielding’s cape. I let the quote soak in the soup that is my brain as I find Jenny and sit down.

Jenny has a wonderful warmth about her, I wanted to nestle in close to her – but felt this might be creepy. So, I sat up straight, crossed my legs (as far as my brash, skin-tight, acid wash jeans would allow) and waited for everyone else to settle down.

The publisher of the book, a man who seemed lovely, but whose name I forget, introduces both Russell and Will and gives us a little breakdown of the schedule. This mission accomplished successfully he heads off to the shadows, or where they would normally be, and allows the limelight of our attention to drift over to the writers of the book. They sit next to each other behind a table displaying the immaculate books, two examples of the editions. One in orange leather with Barrett’s signature in green across the front, and another in emerald green leather with one of Syd’s illustrations of a turtle in brown stamped in the middle, had I £70 that wasn’t already owed to some hideous conglomerate, I would have gone for the latter.

We hear how Will, a renowned Barrett art aficionado, had come on to the book by word of mouth. Brain Werham, a wonderfully dressed man in a jade-green suite who also curated the exhibition had passed Will’s details on and thus, the book as we know it was made. The Q&A varies from repartee between the writers and a woman who went to art school with Syd, questions of what colour the paintings in the black and white photographs were, why they had decided to write the book – which is because when Russell made ‘A Technicolor Dream’ he came across so many of these rare and undiscovered photographs and paintings that he felt they should be shared; and then, all of a sudden, it was my turn.

Automotive Systems are go!

I shoot my hand up. They ask someone else.

Don’t remember what they said, I took it personally and was too busy telling myself not to take it personally to listen to either question or answer.

Automotive Systems recharged, I fling my hand in the air again. I am granted a nod of acceptance, this is it. This is my moment. I direct my gaze at Will and wax lyrical …

“There’s a quote underneath one of the paintings that says “Roger was influenced by Roger” what do you think that says about the variation in his work, that we can see.”

Will says he liked this quote too, good man.

He actually misinterprets my question, but his answer is far more interesting – he goes on to say that although Roger was influenced by Roger some of the variations in his style have been compared to, well, I forget whom. But people who would be interesting if I had the slightest iota of knowledge about art. But Will says he can see consistency in Syd’s work. He has a finer eye than I.

What I actually intended was (in retrospect) to try and get Will to do an Oprah style psycho analysis of Syd; in that if “Roger was only influence by Roger,” and his work is so varied was Roger himself in a constant state of flux or change? Or did the variation in his art say nothing about his instability and reported schizophrenia; he just did what he felt like at the time. But as much against art critics philosphising the meaning behind the artist painting certain things as Miró – I wont even attempt to answer my own question, because it pales in to insignificance really.

The Q&A over we are invited to be shown around the paintings and letters by Will and Russell. I slip out for a cigarette to find Russell and a man who was from the Belgian parliament (as far as I remember) outside. We make jokes, forgettable ones, but oh how we laughed.

I head back in and am introduced to Brain, the man in the jade-green suit who is tingling with excitement. He offers to show me around the paintings but first asks …

“Guess whose suit this was.”

“I don’t know … James Bonds.”

“Kevin Spacey’s”

I smile and he shows me the inside of the breast pocket that confirms, the suit was indeed Kevin Spacey’s. I am suitably impressed, as was Noel Fielding apparently, but then I always knew we shared a similar taste in clothes.

Brain’s excitement is tangible and contagious. I can’t help but get excited. When at first glance, admittedly, a lot of it looked like the random sloshing of paint on canvas – or paper, they reveal themselves to be, after more considered studying and direction from Brian, quite considered. Blobs that look like blobs reveal themselves to be large stones from a park in London, a darker, purple version of the blobs are the stones at night. A little blob inside the blobs is not actually a blob, but a very accurately depicted (in it’s precise colouring) specific type of lichen that grows on the stones. A wash of orange and red in thick acrylic is the burnt orange candle that stands next to it. Child-like skills such as painting over wax are used. Every painting is much more intentional than I’d initially realized. Like his letters it is, in my opinion, their childish romanticism that makes these pictures so, well, I’m going to say it, touching. In the knowledge that he was such an intelligent, sad man, the infantility of his art has a very endearing yet melancholic lilt, to me anyway.

But like I have any fucking idea what I’m talking about anyway.

To read about this man and his art by people who actually do know what they’re talking about, go here ….

And because I promised Brian I’d plug it (that’s right you two readers – mum that includes you,) make Brian’s day and go down, it’s a truly lovely insight in to a small part of a wonderful mans mind ….

http://gallery.ideageneration.co.uk/